imagem: D.B. Dowd, Meet Cockeyed Neil, Sam the Dog Revisited, 2014.

A R.Nott Magazine teve o prazer de entrevistar com exclusividade o professor, escritor e ilustrador estadunidense D.B. Dowd, autor de relevantes pesquisas e publicações a respeito da história da Ilustração e Histórias em Quadrinhos. Em nossa conversa, falamos um pouco sobre a sua carreira, sobre a importância da leitura para um bom ilustrador e sobre o que é (ou o que pode ser), mais exatamente, o trabalho de Ilustração. Confira abaixo!

• Em primeiro lugar, obrigado por aceitar o nosso convite. É uma grande honra apresentá-lo em nossa revista.

Obrigado, Vinicius. Sinto-me honrado pelo convite.

• Como, onde, quando e por quê.

Oh meu deus, é uma enormidade de material! Acho que eu diria, em primeiro lugar, que eu sempre desenhei e que eu sempre escrevi. Portanto, palavras e figuras fariam parte da minha vida, mesmo quando – e por muito tempo – eu não conseguia entender bem como isso funcionava.

O fato é que eu frequentei o Kenyon College em Ohio, que é uma escola de artes liberais. Me formei em História, fiz Teatro e produzi alguma arte também. Foi uma experiência muito rica, pela qual eu me mantenho grato mesmo quase quatro décadas depois. Eu perambulei um pouco por alguns anos depois disso, incerto do que viria depois. Eu escrevi e projetei filmes médicos; pintei tanto casas como quadros; me mudei para Nova York. Vendi bijuterias na Sak’s da Quinta Avenida, e nos meus intervalos eu atravessava a rua para sentar na Catedral de St. Patrick, num esforço de me inspirar para descobrir o que fazer. Finalmente eu concluí que sim, eu deveria apenas aceitar que sou “um artista”, seja lá o que isso for, e que eu precisaria de um maior treinamento visual. Acabei, por consequência, entrando no programa de mestrado em Gravura na Universidade de Nebraska-Lincoln, sob a orientação de Karen Kunc, uma especialista em xilogravura que trabalhava com a tradição japonesa de gravuras Ukiyo-e.

Na verdade, eu não sabia nada a respeito das tradições profissionais ou educativas de design ou ilustração naquele ponto da minha vida. A gravura era a área mais social e democrática das “belas artes”, então foi por aí que eu gravitei. Meu trabalho foi em direção a conjuntos de prints e livros, combinados com textos. Na medida em que eu combinava palavras e imagens, ela correram em trilhas separadas e paralelas. Foi apenas nos últimos 10 a 15 anos que pude começar a ver a mim mesmo como escritor, designer e ilustrador, com projetos sendo construídos mais ou menos nessa ordem.

D.B. Dowd, “Pancake Girl,” spread from Spartan Holiday No. 2: The Five Pagodas. 2013

• Sr. Dowd: sendo você um escritor e ilustrador, eu começo com uma pergunta simples. Um bom ilustrador é também um bom leitor?

Sim! Às vezes a palavra ilustração é usada como se fosse um conceito ou uma atividade eterna. Mas o termo precisa ser historicizado. Tanto a prática quanto a profissão estão intimamente ligados ao advento da alfabetização em massa e da impressão e publicação em escala industrial. Isso pode ser datado por volta de 1850, 1800, ou, se quisermos ser um pouco mais radicais, 1450-1500.

Não há ilustração sem leitura, mas a criação de imagens para narrativas é uma coisa diferente. E para responder a sua pergunta: sim, qualquer ilustrador competente é um leitor atento.

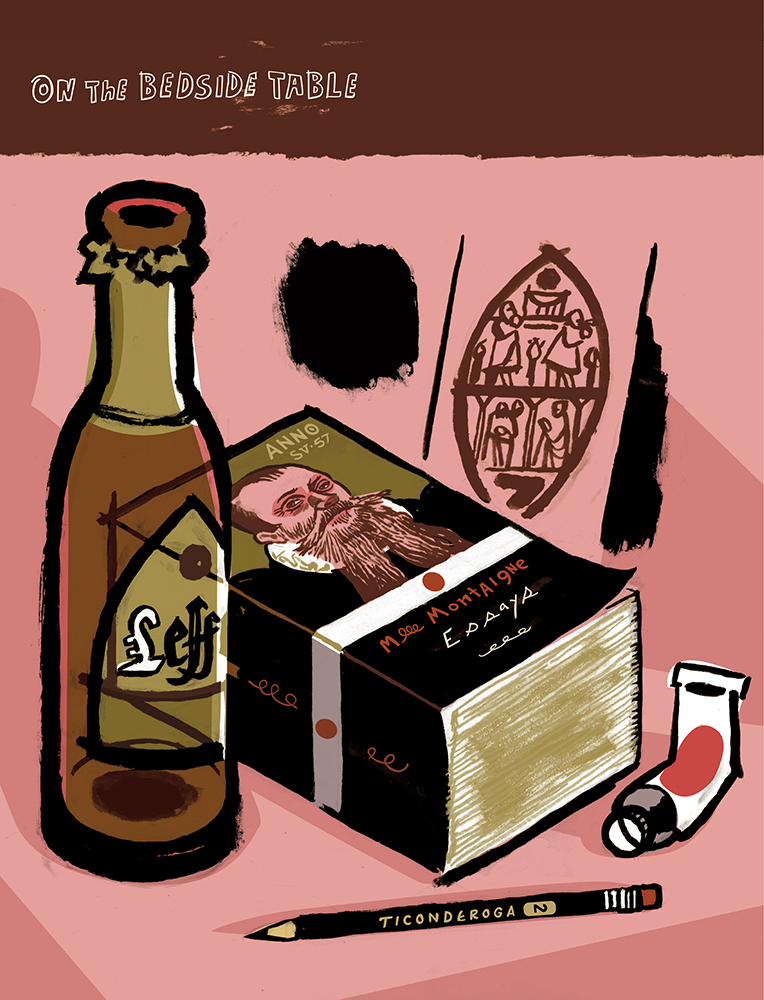

D.B. Dowd, “Montaigne at my bedside,” Spartan Holiday No. 3: French Lesson, 2019.

• Quando entrevistado por Steven Heller em 2019, você disse que o desenho é um tipo de ‘fazedor de sentido’, uma estratégia para permanecer são. Sendo você um escritor, professor e pesquisador, eu fiquei um pouco surpreso (mas também conectado) pela sua afirmação. Você pode nos contar mais sobre esse sentimento? A sanidade não se encontraria, afinal, em textos, mas em imagens?

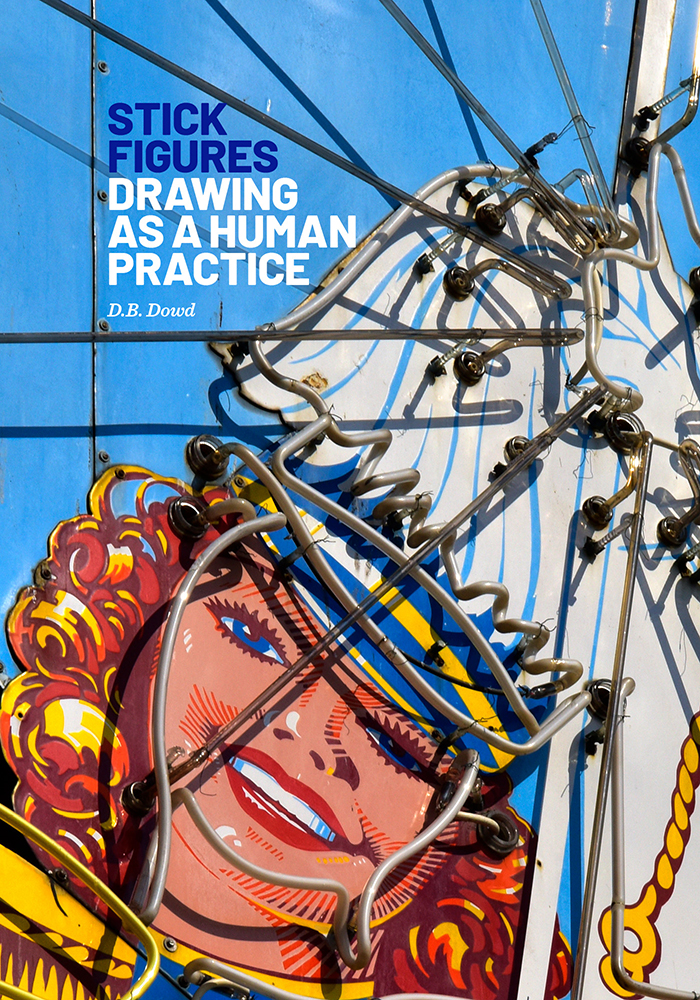

Ah, interessante. Eu escrevi sobre isso em Stick Figures: Drawing as a Human Practice ([Figuras de Palito: o Desenho como uma Prática Humana, em tradução livre] 2018, Spartan Holiday Books em associação com o Norman Rockwell Museum). Desenhar algo (tipo uma bicicleta ou um gerânio) envolve o processo de vir-a-conhecer, de apreensão de um fenômeno. A ideia vai além da observação visual, porque requer um comportamento físico para animar o processo e localizar o lugar do conhecimento. Olhar e marcar são coisas contíguas, não sequenciais; discernimento e diálogo entre o sujeito e o desenho – e olho e mão – conduzem a atividade. Eu traçaria uma distinção entre vir-a-conhecer e o desenho como produto. Descobertas confusas, sem método, não são o mesmo que conclusões esclarecidas. Há, obviamente, um equivalente para a escrita entre rascunho e edição. O gutural versus o refinado-para-apresentação.

De volta à conversa com Heller: de modo pessoal, eu falava também sobre o desenho como método de fundamentação de si mesmo.

• Em seu website, você diz que escreve e ilustra principalmente não-ficção. Portanto, deixe-me perguntar: 1) quais são seus trabalhos ficcionais; 2) quais são seus interesses ‘não-ficcionais’; 3) de onde vem o seu engajamento com paisagens e lugares (o que é que você procura? Por que desenho e não fotografia?)

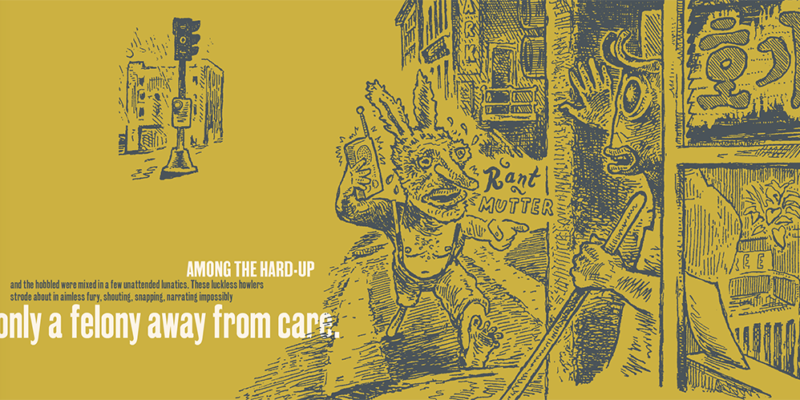

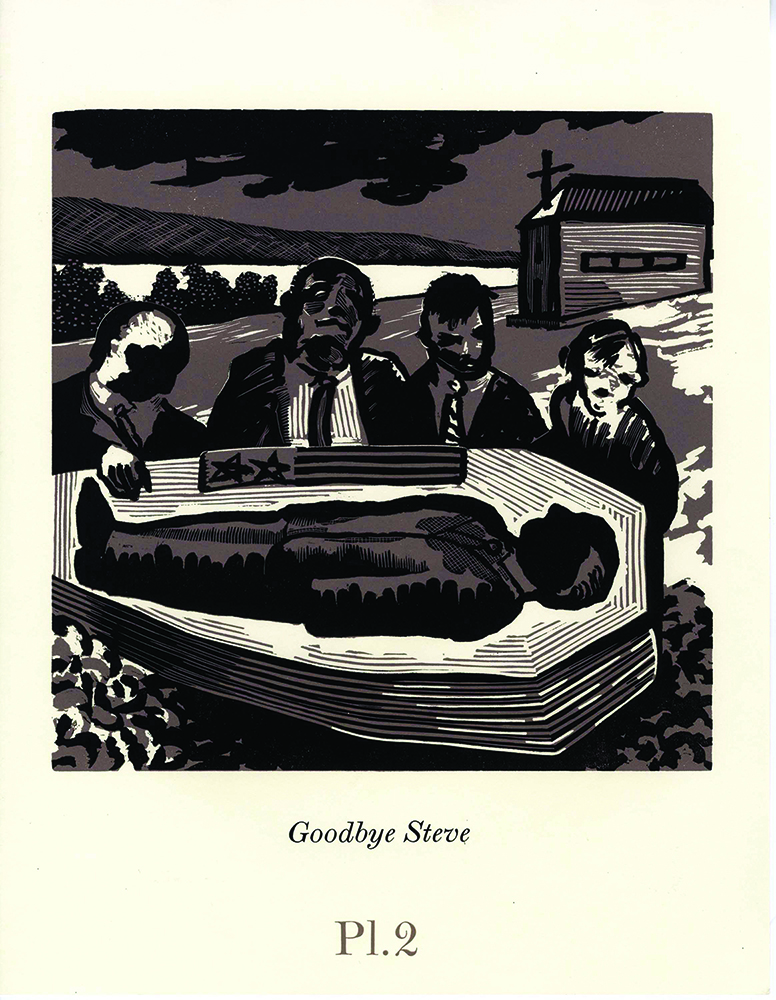

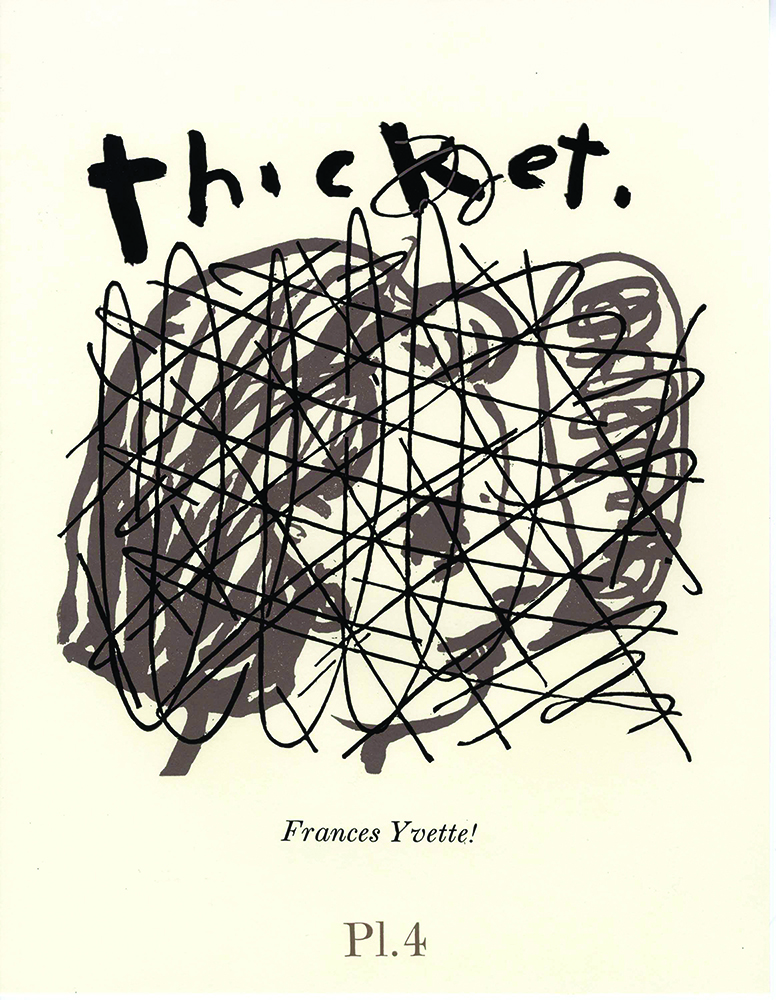

Eu sempre fiz trabalhos sobre cultura, e às vezes tive que disfarçá-los de ficção. Um dos meus primeiros grandes projetos foi um livro não encadernado ‘de caixa’ (no original: book-in-a-box) chamado Cry Mustardville (1995), sobre uma cidade que se despedaça, narrada por um investigador da virada do século (20) que tenta entender o que aconteceu. Foi baseado, em parte, em Bósnia e Ruanda, bem como numa reflexão sobre depressão e ansiedade. Por dois anos (1997-1999) eu produzi uma série ilustrada semanal para o St. Louis Post-Dispatch, que era uma sátira sobre raças e classes chamada Sam the Dog – adorada por uma pequena minoria de leitores mas detestada por muitos mais. Eu produzi um conjunto de gravuras com um texto que acabou por ultrapassar o projeto e virou um romance intitulado Visit Mohicanland (1995-2009) que até hoje eu nunca publiquei adequadamente. É sobre desapropriação e adaptação, entre outras coisas, algo picaresco que envolve viagens no tempo. Eu gostaria de fazer uma edição ilustrada desse projeto em algum momento, já que agora me parece bem oportuno.

- D.B. Dowd, Cry Mustardville, Plate 2 “Goodbye Steve.” 1995.

- D.B. Dowd, Cry Mustardville, Plate 4 “Frances Yvette!” 1995.

Mas na verdade, desde 2010 eu tenho me comprometido com ensaios de não-ficção, tanto escrito quanto visual, como uma forma. Minha revista Spartan Holiday (“Despachos da estrada e notas sobre cultura visual”), publicada de forma intermitente, opera em parte como história, parte como redação de viagem e parte como livro de memórias. Eu estou interessado em saber como as pessoas produzem sentido na era de produção em massa e experiência digital, mas meu comprometimento é com o artefato. Com coisas, lugares. Sinceramente, eu amo a aparência das coisas, especialmente coisas caseiras como fios e aberturas para ventilação e sinalização vernácula. Estacionamentos. A baixeza da experiência tecida numa discussão. Com relação à sua terceira pergunta, eu sou fascinado pela relação entre a fotografia e o desenho, tanto historicamente quanto no presente. Uso ambos os formatos em Spartan Holiday. Esse é um tópico muito mais amplo! Mas o poder de fundamentação do desenho é importante para mim, em um nível puramente comportamental.

D.B. Dowd, Cover spread from Spartan Holiday No. 2: The Five Pagodas. 2013

• Quando entrevistada pelo Illustration Department Podcast, a grande ilustradora japonesa Yuko Shimizu disse num momento que a ilustração não tem a ver apenas com a própria atividade de ilustrar, mas com todas as experiências culturais que vivemos, seja através dos filmes, livros, música, etc., e como eles se refletem no trabalho. A mesma Yuko nos disse, numa entrevista que realizamos com ela em 2016, que ela tenta se manter o mais afastada possível de artistas, sejam eles estudantes ou profissionais, que atuam no mesmo meio que ela. “A última coisa que eu preciso”, disse ela, “é estar influenciada por colegas”. No seu caso, você escreve, já trabalhou com a produção de gravuras, é casado com a Lori Dowd, que é uma cineasta, e tem um poodle chamado Schubert (que referência ao músico, suponho. Corrija-me se eu estiver errado). Dito isso, o que eu quero perguntar é: como ilustrador, você acha que a constante ampliação de suas experiências culturais é uma maneira de encontrar a sua voz individual, em vez de apenas seguir as tendências? Abrir caminhos em vez de segui-los?

Eu sou muito interessado em saber como as coisas são montadas, então os trabalhos em outras mídias me fascinam. Para mim é divertido trabalhar com Lori na StoryTrack para fazer o storyboard de um filme. Já fiz alguns filmes de animação e cartuns online. Eu adoro música e a construção das canções e dos arranjos. Por exemplo, o assunto das gravações de versões cover: como você aborda melodia e letras que já existem e faz uma nova versão disso? Como Cassandra Wilson e Dwight Yoakam produzem abordagens completamente diferentes, mas igualmente envolventes, da canção Wichita Lineman (escrita por Jimmy Webb) após a versão de Glenn Campbell? (e sim, Schubert recebeu seu nome por causa de Schubert).

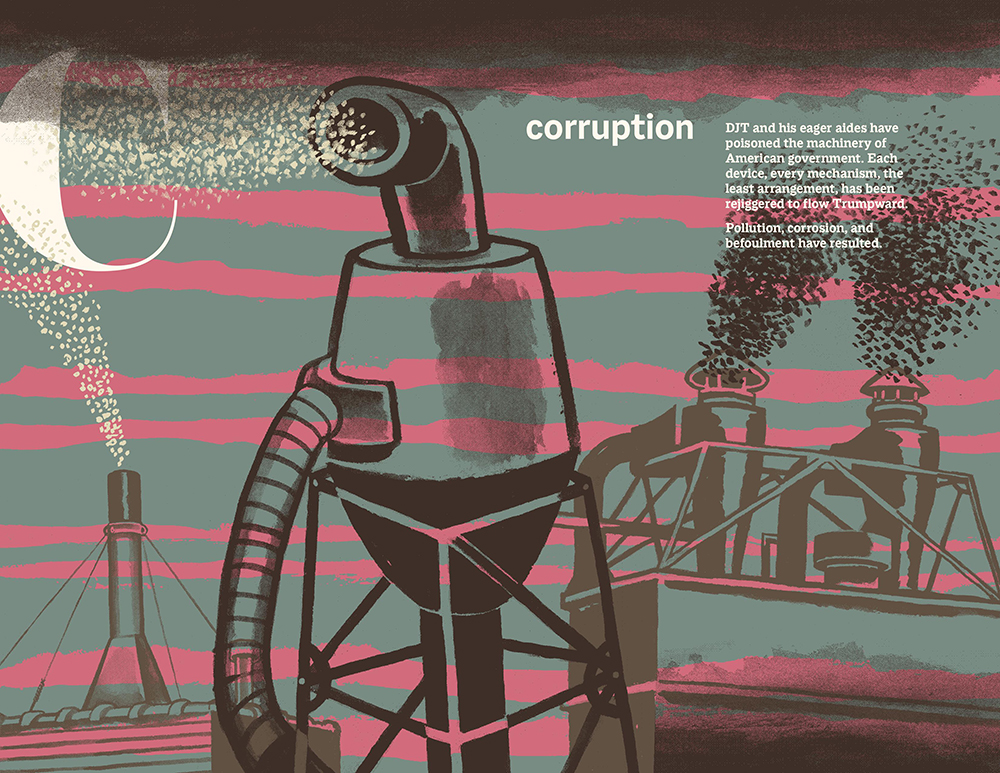

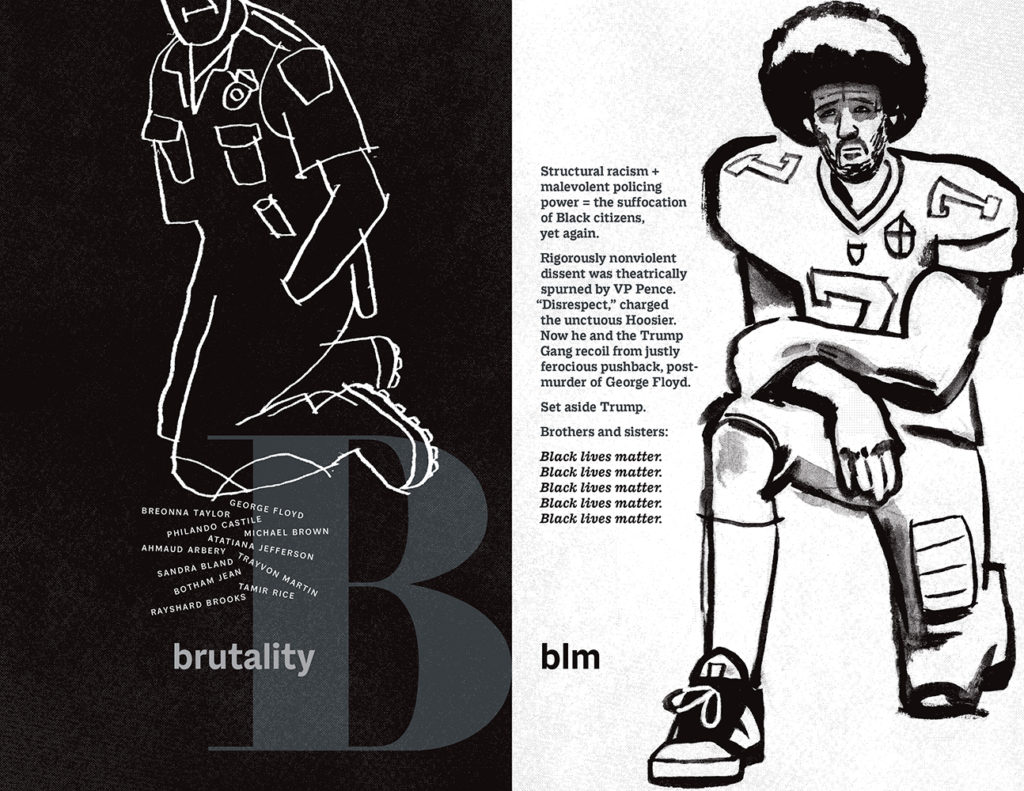

Trabalhos colaborativos aumentam o nosso senso de estrutura. Eu trabalhei com o designer gráfico Scott Gericke em vários projetos, mais recentemente em A is for Autocrat: A Trumpian Alphabet, ilustrado (Spartan Holiday Books, 2020). Essa foi uma colaboração particularmente rica, já que Lori dirigiu os curtas-metragens e as redes sociais que usamos para promover o projeto.

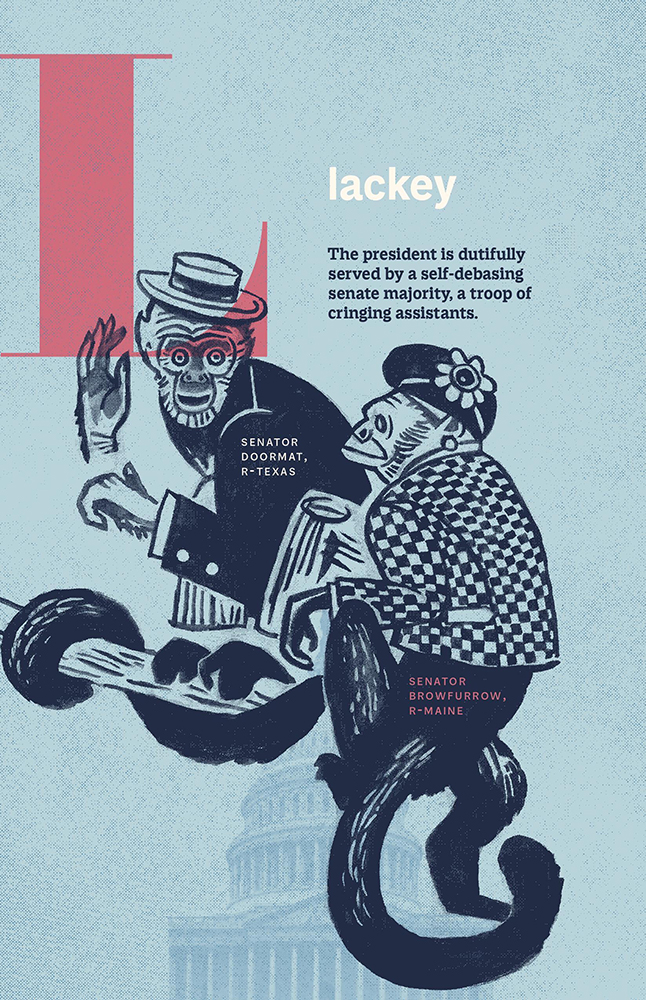

D.B. Dowd, “L is for Lackey,” A is for Autocrat, 2020.

Outro dia, passei cerca de uma hora olhando para as capas de José Carlos feitas para a revista Para Todos em 1927 (veja exemplos aqui). Coisas tão lindas! O que eu acho interessante em seu trabalho (e nos de outros) é a interseção de – e a tensão entre – descrição e abstração. Carlos inclina-se mais fortemente para a abstração do que eu, mas eu sinto que opero nesse espaço, de forma criativa e imaginativa. Eu reconheço e acolho a autoridade do mundo, mas me recuso a ser considerado um idiota por isso.

Eu observo o trabalho de pessoas mortas mais do que observo os meus colegas. Os extintos são menos complicados e o problema da transposição é mais interessante ao longo do tempo.

• No mesmo Illustration Department Podcast, você teve uma conversa muito interessante (e muito controversa) com o Sr. Castellano a respeito do tópico “a Ilustração pode ser considerada Arte?”, e a sua resposta foi “Não”. Em 2015, nosso colunista convidado Marlon Anjos escreveu sobre o assunto, contrastando o artista e o ilustrador, comparando-os às figuras míticas de Prometeu e Epimeteu, respectivamente, dizendo: “O ilustrador recebe o mundo, o artista codifica. O ilustrador trabalha com ordem, o artista com a transgressão.” Por favor, comente sobre isso. (Se me permite, vou estender a pergunta ainda mais: a Ilustração pode ser transgressiva de alguma forma?)

Oh, que ótima pergunta para uma entrevista! Poderíamos passar horas nisso. O Sr. Anjos se baseia na análise de Nietzsche (em O Nascimento da Tragédia) para invocar o Dionisíaco, que é caótico, delirante, descontrolado. A tradição concorrente a essa (que Nietszche considera tediosa e Anjos deixa de fora) é a Apolínea, impulsionada pela “Ordem”. Eu escrevi longamente sobre isso em Stick Figures, numa tentativa de teorizar sobre uma abordagem simbólica ao desenho, investida em epistemologia e conhecimento, versus o antigo ilusionismo da pintura, aliado à ontologia e à experiência. [Para referência: o modo glífico (simbólico) se alinha com a sensibilidade gráfica; o modo vedútico (de veduta, ou visualização) se alinha com a imersão do cinema e a Realidade Virtual.]

Quanto ao enquadramento do Artista inovador e transgressivo versus o Ilustrador obediente e zeloso, eu não sei. Me parece que a romantização do artista/herói/xamã se tornou obsoleta. E quanto ao ilustrador? Não se pode negar que a ilustração como uma obra cultural foi pouco teorizada. O campo sofreu por isso, principalmente por causa de um excesso de entusiasmo e súplica por status. Acho que é seguro dizer que a ilustração é coletiva ao invés de autônoma. Ou seja, a ilustração está embutida em outras coisas, práticas, pessoas. Ela participa, amplifica, reifica, torna legível. Isso a torna insuficientemente heroica no sentido modernista? Okay, tudo bem: a Ilustração não é heroica. Pessoalmente, eu considero o investimento em (super)heróis uma coisa bastante ingênua, então… melhor assim.

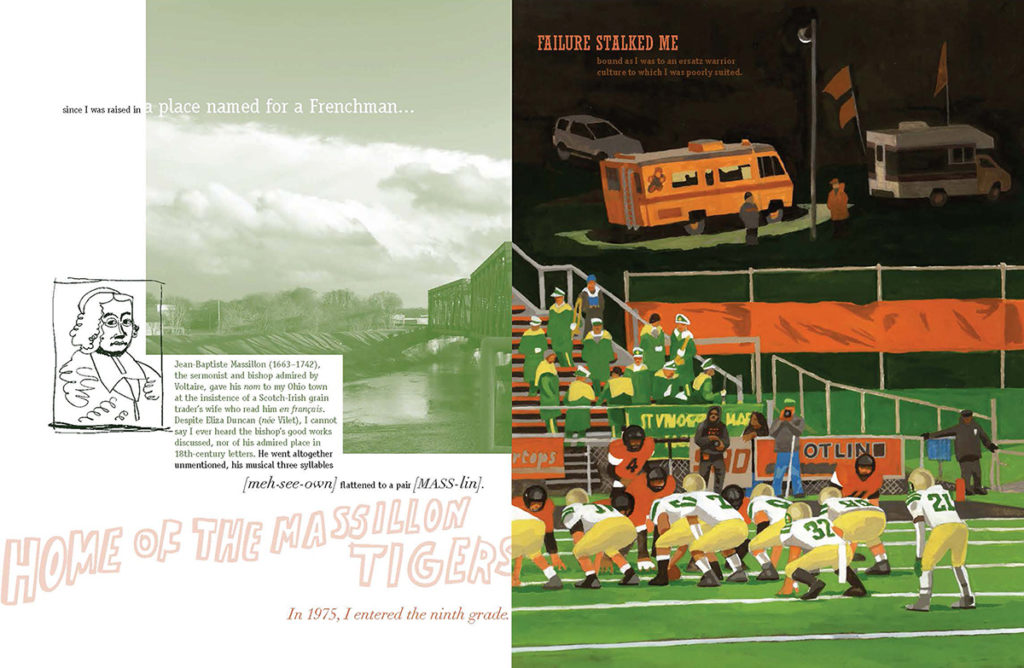

D.B. Dowd, St Vincent Game spread from Spartan Holiday No. 3: French Lesson 2019

• Fale um pouco sobre as suas publicações. Elas são resultados de pesquisas acadêmicas, são ideias e interesses seus, são planejadas com antecipação ou desenvolvidas durante o processo? Estou especialmente interessado no livro chamado Stick Figures: Drawing As A Human Practice. Como ele nasceu?

Stick Figures é um projeto profundamente ideológico, realizado para construir um entendimento teorético de práticas que são básicas para ilustradores, cartunistas e designers gráficos. Entre outras coisas, eu quis resgatar o desenho de seu aprisionamento numa gaiola estética. É uma atividade instrumental. Não requer experiência. Todas as pessoas o fazem.

D.B. Dowd, capa, Stick Figures: Drawing as a Human Practice. 2018.

• Você acha que existe um ‘estilo Americano de ilustração’ se fizermos uma comparação com trabalhos produzidos em outras partes do mundo? Se sim, você acha que isso tem a ver com o mercado editorial?

Eu não estou interessado nessa questão. O que eu acho é que a adoção universal de ferramentas digitais contemporâneas e a onipresença das mídias sociais estão levando ao que eu descreveria como uma generalização Adobe-ficada de formas e linhas, e algo que eu tenho lutado para definir. O que é? A arte da Amizade? Um monte de humanos de aparência amigável e personagens adoráveis e repetidamente destemidos, geralmente feitos em paletas que parecem muito padronizadas. Baseado no que eu vejo online, isso parece um fenômeno internacional, mas talvez eu esteja errado. Só sei que isso me dá vontade de ir até a lama desenhar com um pedaço de pau retorcido. Mas tento manter essas coisas apenas para mim mesmo.

• Quem são suas principais influências e heróis? (e pessoas que você inveja).

Eu admiro tanta gente que nem sei como organizar isso, mas tenho proximidade com escritores e críticos; ilustradores, pintores e cartunistas; e cantores, cineastas e dramaturgos. Um punhado de pessoas que permaneceram significativas pra mim por muitos e muitos anos: Ben Shahn, Susan Sontag, Stuart Davis, Philip Guston, June Christie, Harry Beckhoff, Donald Fagen, Chester Gould, Jim Jarmusch, Johnny Hartman, Ivan Brunetti, Robert Weaver, Chet Baker, e, pelo menos, três pessoas que levam o nome Wilson: Nancy, Cassandra e Brian. Ao olhar para essa lista, vejo franqueza, rigor, acuidade, refinamento e um certo lirismo que vai do ensolarado ao sombrio. (O fato de eu escrever sobre e colecionar o trabalho de gente ativa entre 1920 e 1960 obviamente tem algo a ver com o meu quadro de referências.)

D.B. Dowd, “C is for Corruption,” spread from A is for Autocrat: A Trumpian Alphabet, Illustrated. 2020.

• Eu não posso evitar essa pergunta: como você se sente tendo a Biblioteca de História Gráfica Moderna da Universidade de Washington (Modern Graphic History Library, Washington University) nomeada em sua homenagem?

É estranho. Eu sou infinitamente grato a Nancy e Ken Kranzberg por doarem a biblioteca em meu nome, então é um equilíbrio entre o desconforto de “The Dowd” com o meu alegre dever de avançar o nosso trabalho de maneira coletiva. Eu trabalho com colegas maravilhosos, incluindo a curadora Skye Lacerte, a gerente de coleções Joy Novak e a arquivista de projetos Andrea Degener. Nós fazemos um importante trabalho para preservar e divulgar o legado de ilustradores e cartunistas, incluindo os contextos profissionais em que atuaram.

• Quais são seus projetos futuros?

Estou pesquisando um livro de ensaios sobre estudos de caso em ilustração e cartuns, começando o trabalho numa edição expandida de Stick Figures, e produzindo as edições 4 e 5 da Spartan Holiday (previstas para 2022 e 2023, respectivamente).

• Existe algo que você sempre quis responder mas nunca te perguntaram? Se sim, por favor responda =)

Acho que você já ouviu o suficiente de mim!

Mais em:

https://www.dbdowd.com/

https://www.instagram.com/db_dowd/

D.B. Dowd, “B is for Brutality and BLM,” spread from A is for Autocrat: A Trumpian Alphabet, Illustrated. 2020.

English Version

• First of all, thank you for accepting our invitation. It is a great honor to feature you in our magazine.

Thank you, Vinicius. I’m honored to be asked.

• How, where, when and why.

Oh my goodness, that’s a truckload of material! I guess I would say, first, that I always drew, and I always wrote. So words and pictures were going to be part of my life, even when—for a long time—I couldn’t quite figure out how that would work.

As a factual matter I attended Kenyon College in Ohio, a liberal arts school. I majored in history, studied theater, and did some art, too. It was a very rich experience, for which I remain grateful almost four decades later. I knocked around for a few years after that, unsure of what should come next. I wrote and designed medical films; I painted, both houses and pictures; I moved to New York. I sold costume jewelry at Sak’s Fifth Avenue, and on my breaks I’d walk across the street to sit in St. Patrick’s Cathedral, laboring to divine what I ought to do. Finally I concluded that yes, I should just accept that I am “an artist,” whatever that means, and that I would require further visual training. By turns I ended up in an MFA program in printmaking at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, working under Karen Kunc, a woodcut specialist working in the Ukiyo-e tradition of Japanese prints.

I didn’t really know anything about the professional or educational traditions of design or illustration at that point in my life. Printmaking was the most social and democratic area of “the fine arts,” so that’s where I gravitated. My work moved toward suites of prints and books, combined with texts. To the extent I combined words and images, they ran on separate, parallel tracks. It’s only been in the last 10 to 15 years that I have come to see myself as a writer, designer, and illustrator, with projects being built more or less in that order.

• Mr. Dowd: being you a writer and illustrator, I’ll begin with a simple question. Is a good illustrator also a good reader?

Yes! The word illustration is sometimes used as if it were an eternal concept or activity. But the term should be historicized. Both the practice and the profession are intimately tied to the advent of mass literacy and industrially-scaled printing and publishing. That could variously be dated to 1850, or 1800, or if you wanted to be really aggressive about it, 1450-1500.

There is no illustration without reading. Narrative picture-making is a different thing. And to answer your question: Yes, any competent illustrator is an attentive reader.

• When interviewed by Steven Heller in 2019, you said that drawing is a kind of ‘sense-making’, a strategy to remain sane. Since you are a writer, a professor and a researcher, I was a bit surprised (but also connected) by your statement. Can you tell us a little more about that feeling? Is sanity not to be found in texts, after all, but in images?

Ah, interesting. I wrote about this in Stick Figures: Drawing as a Human Practice. (2018, Spartan Holiday Books in association with Norman Rockwell Museum.) Drawing something (say, a bicycle or a geranium) involves the process of coming-to-know, of apprehending a phenomenon. The idea goes beyond visual observation, because it requires physical behavior to animate the process and locate the site of knowledge. Looking and marking are coterminous, not really sequential; discernment and dialogue between subject and drawing–and eye and hand–drive the activity. I would draw a distinction between coming-to-know and drawing as product. Messy discoveries aren’t the same as cleaned-up conclusions. There’s a written equivalent, of course, between drafting and editing. The guttural versus the refined-for-presentation.

Back to the Heller exchange: More personally, I was also speaking about drawing as method for grounding oneself.

• In your website, you say that you write and illustrate mostly nonfiction. Therefore, let me ask you: 1) what are your fictional works; 2) what are your ‘nonfictional’ interests; 3) where does your engagement with landscapes and places come from (what are you looking for? Why drawing and not photography?)

I have always made work about culture, and sometimes I have needed to cloak it in fiction. One of my first major projects was an unbound book-in-a-box called Cry Mustardville (1995), about a town that tears itself apart, narrated by a turn of the (20th) century investigator who tries to make sense of what happened. It was based in part on Bosnia and Rwanda, as well as on a reflection on depression and anxiety. For two years (1997-1999) I produced a weekly illustrated serial for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, a satire of race and class called Sam the Dog–adored by a small minority of readers but detested by many more. I produced a suite of prints with a text that way outgrew the project into a novel titled Visit Mohicanland (1995-2009) that I have never properly published. It’s about dispossession and adaptation, among other things. A picaresque involving time travel. I’d like to do an illustrated edition of that project at some point, as it feels quite timely now.

But really since 2010 I have committed to the nonfiction essay, both written and visual, as a form. My intermittently-issued magazine Spartan Holiday (“Dispatches from the road and notes on visual culture”) operates as part history, part travel writing, and part memoir. I am interested in how people make meaning in the age of mass production and digital experience, but I am committed to the artifact. To things, places. Frankly I love how things look, especially homely things like wires and vents and vernacular signage. Parking lots. The crappiness of experience, woven into an argument. As for the your third question, I’m fascinated by the relationship between photography and drawing, both historically and in the present. I use both in Spartan Holiday. That’s a bigger topic! But the grounding power of drawing is important to me, purely on a behavioral level.

• When interviewed by the Illustration Department Podcast, the great Japanese illustrator Yuko Shimizu said at one point that illustration is not all about illustration itself, but about the cultural experiences you live, whether through movies, books, music, etc., and how they reflect in your work. The same Yuko told us in an interview we did in 2016 that she tries to stay as far away as possible from artists, be they students or professionals, that work in the same field as her. “The last thing I need is to be influenced by my professional colleagues”. In your case, you write, you have worked with printmaking, you are married to Lori Dowd, who’s a filmmaker, and you have a poodle named after Schubert (the musician, I suppose. Correct me if I am wrong). That said, what I want to ask is: as an illustrator, do you think that constantly trying to enlarge your cultural experiences is the way to find your own individual voice, rather than just following trends? Leading the way instead of following one?

I am very interested in how things are put together, so works in other media fascinate me. It’s fun for me to work with Lori at StoryTrack to storyboard a film. I have made ambient animated films and online cartoons. I adore music, and the construction of songs and arrangements. For example, the subject of cover recordings: How you approach an existing melody and lyric to make a fresh version of something? How do Cassandra Wilson and Dwight Yoakam both produce wildly different yet equally engaging takes on Jimmy Webb’s Wichita Lineman after Glenn Campbell’s version? (And yes, Schubert is named after Schubert.)

Collaboration heightens one’s sense of structure, too. I have worked with the graphic designer Scott Gericke on many projects, most recently A is for Autocrat: A Trumpian Alphabet, Illustrated (Spartan Holiday Books, 2020). That was a particularly rich collaboration, as Lori directed the short films and social media we used to promote the project.

The other day I spent about an hour looking at 1927 José Carlos covers for Para Todos (here are some examples). Such gorgeous stuff! What I find interesting in his work (and that of others) is the intersection of–and tension between–description and abstraction. Carlos leans more heavily to abstraction than I do, but I feel like I operate in that space, creatively and imaginatively. I recognize and embrace the authority of the world, but I refuse to be rendered an idiot by it.

I look at the work of dead people more than I look at my peers. The extinct are less complicated, and the problem of transposition is more interesting across time.

• In the same Illustration Department Podcast, you had a very interesting (and controversial) conversation with Mr. Castellano about the topic “can Illustration be considered Art?”, to which you answered “No”. Back in 2015, our guest columnist Marlon Anjos wrote about the topic, juxtaposing the artist and the illustrator, when he compared them to the mythical figures of Prometheus and Epimetheus, respectively, saying: “The illustrator receives the world, the artist codifies it. The illustrator works with order, the artist with transgression.” Please comment on that. (If you’ll allow me, I’ll extend the question even more: can Illustration be in any way transgressive?)

Oh, what a great interview question! We could spend hours on this. Mr Anjos draws on Nietzsche’s analysis (in The Birth of Tragedy) to invoke the Dionysian, which is chaotic, delirious, uncontrolled. The competing tradition (which Nietzsche finds tedious and Anjou leaves out) is the Apollonian. “Order” drives the latter. I wrote about this at some length in Stick Figures, in an attempt to theorize an approach to symbolic approach to drawing, invested in epistemology and knowledge, versus the ancient illusionism of painting, allied with ontology and experience. [For reference: The glyphic (symbolic) mode aligns with the graphic sensibility; the vedutic (from veduta, or view) mode aligns with the immersion of cinema and VR.]

As for the framing of the pathbreaking, transgressive Artist versus the dutiful, obedient Illustrator, I don’t know. It seems to me that the romance of the artist/hero/shaman has gone stale. As for the illustrator? It can’t be denied that illustration as cultural work has been under-theorized. The field has suffered for it, mostly due to an excess of enthusiasm and pleading for status. I think it’s safe to say that illustration is contingent, as opposed to autonomous. That is, illustration is embedded in other things, practices, people. It participates, amplifies, reifies, renders legible. Does that make it insufficiently heroic in the modernist sense? Okay, fine: Illustration is not heroic. Personally, I find the investment in (super)heroes sophomoric, so that’s a plus.

• Tell us about your publications. Are they the result of academic researches, are they ideas and interests of yours, are they planned beforehand or during the process? I’m especially interested in the book called Stick Figures: Drawing As A Human Practice. How was it born?

Stick Figures is a deeply ideological project, undertaken to build a theoretical understanding of practices which are basic to illustrators, cartoonists, and graphic designers. Among other things, I wanted to rescue drawing from its imprisonment in an aesthetic cage. It’s an instrumental activity. It does not require expertise. All persons do it.

• Do you think there is an ‘American style of illustration’ if we make a comparison with works produced in other parts of the world? If yes, do you think it have to do with the publishing market?

I am mostly uninterested in this question. I do think that universal adoption of contemporary digital tools and the ubiquity of social media are leading to what I might describe as an Adobe-fied generalization of shape and line, and something I have been struggling to define. What is it? The Art of Friendliness? Lots of agreeable-looking humans and repetitively plucky, adorable characters, often in what feel like standard-issue palettes. Based on what I see online it feels like an international phenomenon, but perhaps I am wrong. I know it makes me want to draw with a twisted stick in the mud. But I try to keep to myself about such things.

• Who are your major influences and heroes? (and people you envy).

I admire so many people that I don’t even know how to organize this, but I have kinship with writers and critics; illustrators, painters, and cartoonists; and singers, filmmakers and playwrights. A smattering of people who have remained meaningful to me for many, many years: Ben Shahn, Susan Sontag, Stuart Davis, Philip Guston, June Christie, Harry Beckhoff, Donald Fagen, Chester Gould, Jim Jarmusch, Johnny Hartman, Ivan Brunetti, Robert Weaver, Chet Baker, and at least three people named Wilson: Nancy, Cassandra, and Brian. As I look at that list there is frankness, rigor, acuity, refinement, and a certain lyricism ranging from sunny to bleak. (The fact that I write about and collect the work of people active between 1920 and 1960 obviously has something to do with my frame of reference.)

• I can’t avoid this question: what is it like to have the Modern Graphic History Library at Washington University named after you?

It’s weird. I am unendingly grateful to Nancy and Ken Kranzberg for endowing the library in my name, so try to balance the discomfort of “The Dowd” with my joyful duty to advance our work together. I work with wonderful colleagues, including curator Skye Lacerte, collections mangager Joy Novak, and project archivist Andrea Degener. We do important work working to preserve and promote the legacy of illustrators and cartoonists, including the professional contexts in which they worked.

• What are your future projects?

I’m researching a book of essays on case studies in illustration and cartooning, beginning work on an expanded edition of Stick Figures, and producing Spartan Holiday issues 4 and 5 (expected 2022 and 2023 respectively).

• Is there something you’ve always wanted to answer but never been asked? If yes, please answer it =)

I think you’ve heard enough from me!